|

Interview © The Obelisk.net 2010

Haven’t Dreamed Since… All Along

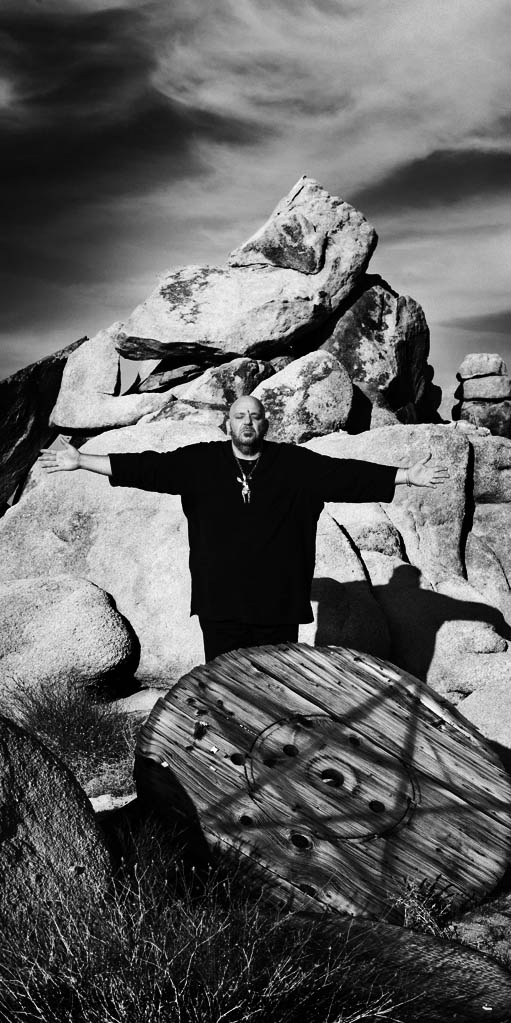

When Masters of Reality frontman and mastermind Chris Goss says “wonderful,” it is as though he has reeled back his whole body to put a breathy and fully human energy into the word. And it is not a word he uses lightly. In the 67 minutes we spent on the phone discussing the US release of Masters of Reality‘s latest album, Pine/Cross Dover, on Cool Green Recordings (it came out in Europe in 2009 on Brownhouse/Mascot Records), he only said it three or four times, but each time he did, I could hear the genuine passion behind it.

Masters of Reality made their debut in 1988 with a self-titled full-length renamed The Blue Garden for its cover art. Throughout the multi-decade tenure of the band, and across albums like Sunrise on the Sufferbus (1992), Welcome to the Western Lodge (1999), Deep in the Hole (2001), Give us Barabbas (2004), Goss has been the lone consistent factor, making his name also as one of the key figures in the rise of rock from the Californian desert as producer and contributor to acts like Kyuss, Queens of the Stone Age, Fatso Jetson and the Mark Lanegan Band, of course helming Masters of Reality from a production standpoint as well.

I’ve been a Masters of Reality fan since hearing Deep in the Hole in 2002/2003 (there are those who swear by the band’s earliest material, but I am not one of them), and whether it’s the driving rock of “High Noon Amsterdam” as presented on the brilliant live album from 2003, Flak ‘n’ Flight, or the rich harmonic texture of “Always” or “Testify to Love” from Pine/Cross Dover, I find that, whatever scene you want to lump them into, they make for a listening experience like none other. After wanting to for years, it was great to finally have occasion to conduct an interview with Goss.

|

In the conversation below, the guitarist/vocalist/songwriter/producer talks about pushing back the release date of Pine/Cross Dover to allow for more time in the studio, working with longtime drummer John Leamy on the album and bringing in guests like Dave Catching (earthlings?) and Brian O’Connor (Eagles of Death Metal), the state of commercial attitudes toward rock and roll, the enduring legacy of the desert scene he helped to found, being arrested in Germany on Masters of Reality‘s last European tour, and much, much more. The interview wound up being over 6,100 words, so there’s plenty to dig into. It’s pretty epic.

You’ll find the complete, unabridged Q&A after the jump. Please enjoy.

The last couple records were European only. How did the US release come about?

Actually, it was a matter of convenience? Mascot Records in Holland gave me my own imprint called Brownhouse years ago to put Masters of Reality. They decided to open a US arm of their label, called Cool Green Recordings. They opened a New York office, and it was like, “As long as you’re opening an office in New York…” because we’ve worked well over the years and they’re not afraid to spend money for promo. It’s not a major label by any means, but they realize certain important things. When I put records out in Europe, I go on a two-week press junket, and that’s usually more than major labels send their artists out to do. I’ve been impressed with them, no pun intended, over the years, and what they did in Europe for us. So here it is. I like the name of the label too. Cool Green. Green’s my favorite color. It’s got nothing to do with the ecology (laughs). They have a guy in the New York office, J.T. Hamilton, who I got along with when we met, and we nailed the deal down.

So is it Brownhouse through Cool Green Recordings?

It’ll just be Cool Green Recordings here in the US, and we’ll see what happens. I don’t look at my career or Masters of Reality as an album cycle. It’s kind of like, that music’s out there forever, and I don’t care if, six weeks from now, whether it’s charted well or not. I will continue to stand by that music for the rest of my life – as with all of our records. Time has shown they just keep going on and on, and it’s been a very, very slow, long process. 20 years since the first record, really, and still, people are just getting turned onto it. And that’s really exciting to me. It’s been a really long, slow payoff (laughs). Kind of like The Ramones, in a way. They never really burst through the top of the charts, but little by little, it was like, “Who the hell is this?” to people out there who weren’t aware of them, they’d be, “Wow, what a cool song that is!” I don’t mind being like that. I don’t mind being like that. I make a good living doing what I do, co-writing and producing with other people, so Masters of Reality is like my own restaurant.

The initial, European, release date was pushed back and you said then you were going back to do more writing. What made you do that and what came out of that extra time putting together the songs?

We do our records very spontaneously. I get together with John Leamy, our drummer, who lives in New York, and in the meantime a few years go by. I accumulate little bits and pieces of ideas on the mini-recorder and have riffs and beats and ideas, blah blah blah, and bring John to the desert – this is what’s happened the last three albums of new material – and we jam. We expound on these ideas and in the process of jamming, come up with 20 more ideas in addition to the 20 or 30 I may have had in the first place. It’s wonderful. It said in the press release, we both were so busy with production all the time of other people’s stuff, that when we get in a room together and we just go, we’re playing ourselves, and for the pure joy of it. It’s just wonderful. It’s us, and it’s what we want to do, and there’s no one dictating anything to us. Totally by instinct. So he comes out for a few years, and we get drum tracks out of the jams, and then I finish the record with vocals and overdubs. This last record that just happened, to answer your question, we got a lot of great drum tracks, and also a lot of jams down on tape, and the task of getting those sorted and edited and made into songs took a little bit longer than I thought. In my world, three or four months for me is a long time to do a

Masters record. In “normal world,” most bands take a year or two to garner enough material to put together a cohesive record. Even though it was delayed over and over again, it really only took, in physical studio time, maybe three months, four months, spread out over a little bit of time. For example, the last song on the record, that long jam session. We had so many of those kinds of jams for these sessions, that to actually go through and say, “Okay, what here is cohesive? What here is enjoyable and is representative of how we feel at that moment?” what we’re proud of, I guess – took longer than it would, normally. The record called Deep in the Hole, I think we polished that off in six weeks. And you’ve got to realize, that’s from having nothing, basically a few ideas for riffs, and then having a finished album in your hand, in six weeks, of pretty good quality. I’ve really prided myself on how quickly we work, no matter what the rumors are or if I needed to go back and get more time and stuff like that. I still work really, really fast in the studio and prefer it that way. In this particular record, Pine/Cross Dover, I was writing while we were mixing. We were putting songs up that just had a drum track, and it would be, “Okay, we’re mixing and recording at the exact same time.” Throwing down tracks, fitting them into the song, throwing down more and the next day the song would be done. It’s a really, really exhilarating way to work. I lived at my engineer’s mix studio for that duration, and we worked till the sunrise every morning, then about one or two in the afternoon, I literally walked from my room to the back of his house where the studio is in the guest house, and in my bathrobe with my coffee, would sit down and listen to where we left off in the morning. It was really, really great to do that. Have my first cigarette and coffee, and hit play, and usually be really happy with where it was left off. It was really exhilarating. I have to give a great big nod to two people: Brian O’Connor from Eagles of Death Metal and David Catching, also from Eagles of Death Metal. I say from Eagles of Death Metal because that’s where most people know them from, but I’ve known them before that. Dave, I should say, is from earthlings?, and Brian too, but Dave’s band is early earthlings?, and he owns Rancho de la Luna Studios out here in the desert, where I do a lot of work. Dave and Brian were there for most of that record. If they weren’t playing, they were sitting there cheering me on, or cooking, or running out buying groceries, or rolling joints. They knew I was alone doing it, because John had gone back to New York, and I would show up every day and Dave and Brian would walk in a few hours later with a bunch of steaks to throw on the grill, and be on standby if I needed them to play in any tracks, which they did play in quite a few tracks. There’s a line in one of the songs, “Rosie’s Presence.” The end of the song, it’s a refrain that says, “Tripping out on the love,” and I really was. That’s a statement of how I felt with those guys hanging around. They were just the best friends. It blew my mind how they were there to support me every day when I was finishing this record. No pay. Just there because they’re so fucking cool.

You describe the process of carving songs out of these jams and these ideas. Was there an abundance of material left over?

Always, yeah.

Did you give any thought to doing a double album?

Always, yeah (laughs). Almost every record we do, the thought comes across: “double record.” And then, I think of Joanna Newsom, who I’m a big fan of. She plays the harp. My favorite contemporary writer. Her last record was a triple record, and I love her so much that I haven’t even gotten past CD one yet and the record came out about a year ago. So there you have it. I think, “Is the attention span out there?” I know I don’t have time to confront a double record in its entirety. Maybe when I’m driving around, that’s when I listen to most of my music uninterrupted, when I’m driving. But to answer your question, yeah, I always think about doing a double record, then always poo poo the idea, because I think it’s just too much. At this period in time, there’s a certain air of quick fixes. People put their favorite songs on their iPods and get these quick shots of bands and hear one song of a band. I’m from an era of albums, where I bought an album every month, maybe, and would listen to that record, sometimes nonstop, for a month. And it would be the only record I’d listen to. I was a kid when Led Zeppelin 4 came out, and the record didn’t leave my turntable for probably six months. That’s how I get stuck on records. I was stuck on Joanna Newsom’s first record like that. It was called The Milk-Eyed Mender. I was stuck on the Deerhoof record called Milkman like that. When DJ Shadow’s record, Introducing, came out in the ‘90s. OK Computer. There’s certain records. I don’t know what it is about them, but I just get stuck there and I just want to hear them every day and it’s about all I can hear. I don’t digest a lot of different music. I do over a period of time, and usually when I’m directed to something, I really hate it anyway. People go, “Have you heard ‘Some Name?’” and I’ll buy the record and check it out and really regret it because I don’t get it (laughs).

I hear that. I get people recommending music to me all the time, and sometimes it’s like, “Really? This? Is this what you think of me?”

Yeah, and there’s just too much of it. I checked out StonerRock.com, I hadn’t been to the site in a while, and maybe one out of eight bands I’d heard of, on the list of articles. I’ll check out bands that have interesting names or something like that, and I’ll hear some kind of revamped sludge jam hard rock à la Hawkwind, and I’m not into Hawkwind. I know a lot of people are, but I need a little bit more structure, and some kind of connective tissue or something like that. I can’t take rambling. So even something like that. I have a very particular slant with the shit I listen to, and it’s kind of hard to explain what it is. I think it’s songwriting. I’m looking for really unusual and well-crafted songs that keep me interested. Even if they’re obtuse like Bowie’s ‘70s stuff. I’m still enamored with David Bowie from 1970-1981. I can’t stop listening to Low, Heroes, Station to Station, Scary Monsters, Young Americans, Diamond Dogs, any of those records. The change from one record to the next. And there’s a lot of instrumental, experimental stuff on those records, and he was just such a pioneer. It’s not pop songwriting, but it sure is interesting. I guess certain musicians tickle you the right way.

You put a lot of that into Masters of Reality too, though. Songwriting and structure. I’ve always felt listening that that’s been a focus for you in the band.

There’s a lot of Bowie influence in the writing, no doubt. And a lot of Led Zeppelin. Since I was a kid, Led Zeppelin. In the order: Beatles, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie and compositions by Jon Anderson, the singer from Yes when Yes was really great in the ‘70s. Those are probably the four that I’ve been obsessed with my whole life.

You cover a lot of ground there. Beatles pop songwriting, Yes is more prog, Led Zeppelin is hard rock and David Bowie’s the weird.

I always compare them to painters. Bowie’s the Picasso, and Yes is the epic Botticelli, Led Zeppelin is maybe Dali. Kind of scary and twisted. And The Beatles. Shit. Maybe they’re Andy Warhol (laughs). They took everything, digested it, spit it back out.

What has made you keep Masters of Reality as just you and John and everyone else as guests?

Availability of people, really. I do Masters records on a whim, and when the time is right for John and I to get together. And when that happens, the other musicians that I really like to play with may or may not be available to do that. It’s kind of a floating lineup. It’s so weird, because I feel like my band is run like a band that I would hate if it was someone else’s band. David Bowie being the exception, because he uses different musicians all the time, but the element of the audience falling in love with certain band members and players in a band – I think it’s kind of hard to get used to for some people, but the band changes a lot. It is a matter of availability and also people’s ability to keep up with John and I. We’re usually pretty concurrent and pretty understanding of where each other’s playing is at that particular time. Before we get together, I’ll give John a rundown of what I’ve been listening to and the type of slant, the angle we want to take on the record, and he’ll know exactly what I mean. And the same with my engineer I work with most of the time. You find people who understand your language, and know what you mean. I think the records I did with Jeordie White, the Goon Moon records I’ve done with Twiggy or Joerdie, whatever you want to call him. They happened really quickly too. We both just concur together when we’re making music and get the vibe of what’s going on. A lot of times, when you jam with people, they’re not in the stage that you are. If I’ve been listening to a lot of fusion at a particular time, which happens – I pulled out a lot of fusion records I loved when I was a kid; Weather Report and Mahavishnu Orchestra and Herbie Hancock – and if I get into a stage where I’m just listening to those kinds of records every day, that comes out in my playing, and it comes out in my jamming and the way I’m going to approach music. If I’m playing with someone who’s been listening to KISS for the previous six months, you know, we’re not going to gel very well. I usually am looking for someone who has a wide listening appreciation. You say “fusion” to some people and their stomach turns, and that’s very unfortunate, because they don’t know what they’re missing. Or you say “prog.” The amount of great music out there that people don’t know about. There’s some King Crimson records that every good musician should know backwards and forwards, and I just find as time goes on, there are references made by other musicians that I don’t understand, and I’m sure they don’t understand a lot of my references either. I wasn’t a Black Flag fan. And so, if I’m gonna be playing with someone who’s a huge Black Flag fan, then we’ve got problems. I know Mario Lalli, who’s a musician who’s lived in the desert all his life, likes Black Flag as well as all the prog stuff I like, so I can jam with Mario no problem. It’s just hard to gel with people sometimes. I just had a great jam session with Barrett Martin, the drummer for the Screaming Trees. For two days we jammed here in the desert recently. He’s spent the last 10 years bouncing around from Africa to South America studying rhythm and hallucinogenic spirituality, and so we clicked instantly. We’d never jammed together before, and it was just wonderful. Sometimes it happens where someone just floats into your life and you click musically with them really, really well.

How did that come about? Are you guys going to make a record?

I’m sure we will, actually, because in about six hours of jamming in two days, which all was captured, there’s probably 15 great sections. 15 great grooves within that six hours that go on and on, and I’m sure we’ll be doing more stuff together. He’s already planning on coming back. That’s the key for me. John Leamy, who’s drumming better than he ever has in his life – he’s become like a Billy Cobham now – we just click so well and immediately take turns at the same time when we’re jamming. The jam that’s on the record, “Alfalfa,” you’ll hear these sections start and stop like they were written, and those were completely pulled from outer space at the moment. Those were not planned out. Those things were basically the four of us, but especially John and I, clicking, and the other guys clicking with us. And man, people hear that and I take some shit for putting that jam on the record. “It shouldn’t been a bonus track,” and all that kind of shit, but I hear that and think, “Okay, well, you really don’t know what went down and you’re really not listening to that.” Also learned when doing that jam how some of my favorite music was made. How some the Weather Report records and Mahavishnu records and jazz records were made. Just by accomplishing that particular piece of music, I really went, “Ah, that’s how they did it.” And it basically was editing. You jam and if a part went on too long or something like that, you chop off some of the fat and there you have it.

I think some of the criticism you’ve gotten for having “Alfalfa” on the end of the record like that – and I haven’t seen all the reviews, I’m just talking off the top of my head – is it’s structurally different from the rest of the record. It’s coming from a different place.

Yes. Good point. Yeah, it’s like, “Where the fuck did this come from?” Yeah. I understand that. I can understand that, but what else do you do? I could put it away, but when would it ever fit in? That’s how I look at it. I was really happy listening to it, and said, “Well, I want to share it,” and that was it. I suppose it was a left turn that most people couldn’t quite understand, because they weren’t there. “I guess you had to be there,” kind of a thing musically.

I’m trying to remember what I said when I reviewed the album, but the vibe I’ve always gotten from that track has always been, “Well, this sounds like a lot of fun.”

You got it (laughs).

Working with different players, obviously someone brings something of their own, is it different for you working with someone like Dave Catching, who has experience on the other side of recording like yourself? In terms of overseeing it?

Not really. It just happens, and things happen when I’m jamming with Dave, and things happen when I jam with Mark, and most of it’s good, and what isn’t doesn’t get heard anyway. Mark’s a very, very trained player. He’s like a country picker, who never puts his guitar down all day, and there’s a part of him that really understands also Steve Howe’s guitar playing, the guitarist from Yes that I really like, and so Mark can play all kinds of stuff that’s very technically apt. I’m not. I’m trying more to be lately. I’m playing my guitar right now more than ever. Then there’s guys who are straight-ahead rock players that are also brilliant in what they do. I suppose it’s kind of like the difference between loving James Williamson with The Stooges and Ron Asheton’s playing, and being able to love The Stooges and The Ramones and also being able to love John McLaughlin and Steve Howe and Robert Fripp, and also loving Billy Gibbons’ and Ronnie Montrose’s playing. Different characters who do what they do really well. An open mind for music, no matter what its format, and being able to hear genius in The Ramones and being able to hear genius in a lot of prog music too, that’s where I’ve always been as a music listener. I’ve always listened to everything. Classical music. There was a period in the ‘60s and ‘70s where classical music was hip to listen to, because you knew some of your favorite writers were listening to Stravinsky and Beethoven. The Clockwork Orange era. The Stanley Kubrick stuff from 2001: A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange, where classical music plays an integral part in the film. What happened was a lot of kids got turned onto classical music because of those films, and that’s maybe scarily lacking right now. The kids aren’t able to recognize the opening bars of Stravinsky’s “Firebird Suite” or “The Rite of Spring.” That used to be very common knowledge at one point, believe it or not. “Stoner rock.” In 1973, when you were a stoner, it would be very normal to put on Frank Zappa or Stravinsky along with Pink Floyd and other classical composers. It was very normal to be doing that when you were hanging out with your friends. When hard rock turned into championship wrestling to me, sometime in the ‘80s, when it became all image- and costume-based, that was when stupidity reigned. I think Beavis and Butt-Head made fun of that. It became cool to be retarded, and not retarded in a genius way like The Ramones or Dee Dee Ramone. Like championship wrestling. Music turned into that. Stupid and fake. Like fake blood, where Iggy Pop was real blood and you knew it. When it got fake, it got stupid. I think we’re still really paying for that stupidity right now. The quality of the rock that’s on the radio, it’s unlistenable at the moment. I cannot listen to Nickelback and Creed and Daughtry and Simple Plan and whoever is out there right now. I just can’t. It’s unlistenable to me. Where’s the brave new world here? It’s canned angst, and they’re selling this phony rock. It sounds really phony to me, and no one’s taking any chances. So fuck ‘em. I have what I like, and that’s it.

At the same time, I think the tradeoff is there are a lot of great and interesting things being done, but it’s not given the same kind of commercial push, commercial exposure, as your King Crimson, Yes, and those bands were. There are bands out there doing amazing work, but you have to find it.

There’s just too many. There’s too many to sort through. That’s the problem, and it does go back to the ‘80s and the signing frenzy. And now, everyone has ProTools in their bedroom, so there’s just so much music being recorded and released, and 99 percent of it, maybe, is shit. To sort through for that one percent, that’s a tough thing. It’s really hard to do that right now. Bands come to record with me and they’ll make a reference to a Killers song and I’ll say something like that, and I still don’t know what they’re talking about. I have to actually download the song from iTunes and hear it, because there’s just so much stuff out there. You’re right. There is great stuff being done, but yeah, it’s just finding it. Having the wherewithal to find it. That’s the key.

It’s easy to be discouraged, like you say, by radio and commercial rock. I’d imagine all the more so for someone like you who has produced bands for a long time and has seen these changes first-hand. I’m pretty much just a fan.

Yeah. It’s kind of like I’ve been spoiled. I was born at the right time where I got to see a transition. All these musical transitions happened very naturally, and as they happened, they led the listener through these different eras. Sometimes the eras were only two or three years long, but to know psychologically and aesthetically, all these changes that happened and how our minds grew with what we were listening to, and seeing that process, I’m really, really fortunate to have seen that and experienced it and to be able to clearly sense how it happened and how it might happen again. Because things are cyclical, and I think the curious mind of an intelligent 15 year old is exactly the same now as it was then. They’re even smarter now. I’m amazed at the intelligence of younger people who are actually onto shit, and how fucking smart they are. I consider myself pretty stupid and lazy in reality, and I still learned a lot, and then I see kids who have brains and listen to them speaking about stuff and I’m blown away by how smart they are. I do have faith that the cream will rise to the top, that, you know, kids will sort it out. They will sort it out. Give them some time, and they’ll find the best shit.

What do you think of the way that the desert rock, desert scene – Kyuss, Queens of the Stone Age, Mark Lanegan, Masters of Reality – has been adopted around the world?

Boy, it really has been. I hear it in everything. Obviously, if you’re doing six degrees of Kevin Bacon, you don’t have to take it that far with the work we’ve done. It goes back to Nirvana. Nirvana were huge Kyuss fans, and we knew it at the time and I started hearing Kyuss in Nirvana, and I started to hear my work with Kyuss in Nirvana, and take it from there. Nirvana set a million ships asail, and I think rhythmically, that’s the biggest influence. The rhythm. That’s why I liked Kyuss, mainly. They had a lot of swing, and there’s a certain slant to the rhythm of the things they did. So if it influenced Nirvana, and obviously Foo Fighters, Dave Grohl’s connection to it all, then there you go. It landed then, and I think the world knows about it. I have musicians who come to the desert to work with me, and it’s funny. We start working together, and they hear the stuff that I start to add to their music, and then they start realizing, “Oh shit, yeah, those harmonies.” That particular way of looking at harmony and rhythm, and if you get an ear for it, even the grunge movement – I had that fucking word; I hate all these words (laughs) – but it got influenced a lot by what we were doing here, and now in the world of electronica, with UNKLE and Massive Attack, you can hear the desert influence happening in worldwide DJ music too. I hear it everywhere, I guess because I know it. It’s like a flavor. A flavor I know really well, and it’s like, “Ah, there it is.” It could be a little turn or instrumentation in a song, or a repetition, or a certain heaviness, a particular kind of heaviness, and yeah, it’s all over the place now. The cat’s out of the bag.

I’m glad you brought up UNKLE since I wanted to ask about “Testify.” That’s probably my favorite song on the record. I know you’ve worked with them before, but how did bringing them into that song come about?

James Lavelle, at the time I was doing my record, he said, “I have three or four tracks I want you to work on. If you have some time or you’re in the studio, ha ha, check out some of these grooves.” He sent some stuff over by email, and there was this one particular groove that was “Testify,” and especially the chorus. The chorus is “Hold on,” and I really liked that feel [in the music]. There were four songs he sent, and I said, “You know what? Just let me use these parts from this one particular song.” And I think, I’ve forgotten the name of it at first, it was something about the night (laughs), and he ended up calling his record Where Did the Night Fall, so maybe that’s what he was referring to, but he was like, “Where’d my song go?” I forgot the name of the original track, but I was like, “Here’s the song.” It was 12 minutes, a dance thing. There were three minutes at the front of it I thought was the whole song, so I just took that three minutes and developed that three minutes further. I‘m glad you liked that one, man. It is a good one, and I think it also indicates how Lavelle, how his songwriting has really matured, from DJ — almost like Andy Warhol, taking someone else’s work and replicating it — sampler guy, to actually having song visions now. That was just a nice complement to each other.

One more thing I wanted to ask about was the liner notes. I don’t know if the art is going to be the same for the American version of the album.

Yes, it will be.

Can you talk a little bit about the liner notes you made for the songs and the setup, where you’re on the beach writing them? What brought that about?

Very odd. I still really am not sure I did that (laughs). It’s very uncharacteristic, and I don’t like to expound too much, especially on a record cover, but there’s something that said, “You have to talk this time. You have to let people know what’s on your mind.” I don’t know what it is. I think we’re at this really strange crossroads in our evolution at this moment. We’re at this strange point in communication. We’re in uncharted waters. Hence the water reference, I think. We’ve never been in this position of the world being connected so instantaneously, and what the implications of that are, there’s beauty and horror in the implications of this situation we’re in. Opportunity and total destruction are closer than ever before. I think that flipside of where we’re at as a species, it’s why the record has two covers. One is pretty creepy, with the bell falling in the ocean. That was like hopelessness and being in a storm. And the other side is this pine, which I think has a double entendre at work. Almost half-excited and half-terrified. That’s what I’m feeling in the air, and I think at the time, and still now, I don’t regret those liner notes. Like I said, it was something I’d never do and I’ll probably never do again, but it just felt like it was the time. It was this freezing day in May on the ocean, which was very strange and that’s what came out of the notebook. The notebook was soaking wet. The Sharpie was blurred all over the pages of it, and I was literally sitting on the rocks writing that, and it was just really weird, at that moment, thinking that only 50 centuries have passed since the pyramids. It’s not much, when you think about one century going back to 1910 right now, to basically man learning how to fly. One century. 100 years ago, where we were as a species, and where we are now. And 50 of those one centuries is nothing. 100 years went by. People are still alive from 100 years ago. So 50 of those lifetimes is as far back as we know. It’s about 5,000 years, really, aside from maybe ancient Sanskrit, that’s about how far we can trace our history back, and it’s nothing. It just struck me at that moment. What happened? It changed really, really quickly in the last 100 years, and these changes, the implications of it all, what’s it mean? Is this it? And if it is, we probably deserve to have our asses kicked for being so stupid. I guess it was just a weird ponderance. A very strange thing to do, and like I said, it was completely spur-of-the-moment. I asked John, after I wrote it, I sent it to him and said, “What do you think, is this too weird?” and he said, “Dude, if you’re feeling it, say it.” So there it was. So yeah.

When it comes to playing live, do you have anything planned?

I’m actually meeting with my agent tomorrow, and I think there’ll be tour dates to be announced for this year, for the US. Not many, maybe only seven or eight shows, but yeah, we’re gonna do some US shows this year… I want to play so bad, and the last European tour we did in the Fall was really, really not right. The rehearsal situation was a nightmare. We decided to rehearse in Holland, and the logistics were terrible, and we had gear that was blowing up and everything that could possibly go wrong went wrong. We were locked in the building all night. It was ridiculous. After the first show, we were arrested by the police in Germany, and six hours late arriving to the second show. One of the biggest shows on the tour was the second show, and we were supposed to go on at 10 and we got there at nine, no soundcheck, completely frazzled after being harassed by the German police for hours. That was the whole tour. After about four shows, we got our groove on and then you forget the problems when you’re grooving, but yeah, it wasn’t the show I wanted to do. I wanted to do a lot more material than we presented at the time, and so it was like getting the shit beat out of you and then saying, “Okay, go play for two weeks.” That’s what it was. These American shows, I want to confront a bunch of material that I wanted to do in Europe, but we couldn’t for time purposes. Just didn’t have time to get into the intricacies of it. And especially for fans in the US. We’ve probably been crueler to our fans than any band ever, as far as letting them down from time to time. It’s almost a consistent one letdown after another. And that bothers me. It bothers me. I feel like we rarely play in the States, and I can’t wait to fucking play.

There was a long delay, years, leading into this album. Do you find that with it out in Europe and now the US, are you inspired to do more with Masters of Reality?

Oh yeah. Absolutely. Not only am I inspired to do more, I think it’s what I’m going to be focusing on. The happiest I am is when I have my guitar in my hand, and that’s all there is to it. I’m not getting younger, but as long as I can play my guitar, I’m going to. That’s where I’m at. I just want to play, and basically go blow everyone off the fucking stage that’s out there right now. I could sit here and talk about how shitty bands are, but I’d rather go out there and show them how to fucking do it. That’s what I’m about to do.

Any other upcoming projects? You mentioned Goon Moon before. Is there going to be another Goon Moon record?

Yeah, there’ll be another Goon Moon record. It’s our schedules once again, and we come close to it and then either me or Jeordie gets pulled off to do something that we can’t say no to, a tour or an album with somebody. But yeah, there will definitely be Goon Moon records. We really have a gas doing those records. Laughter is the biggest part of those records when we’re making them, and I really want to keep working with Jeordie. Maybe I can talk him into being the bass player in Masters, I don’t know. That would be wonderful.

|

|